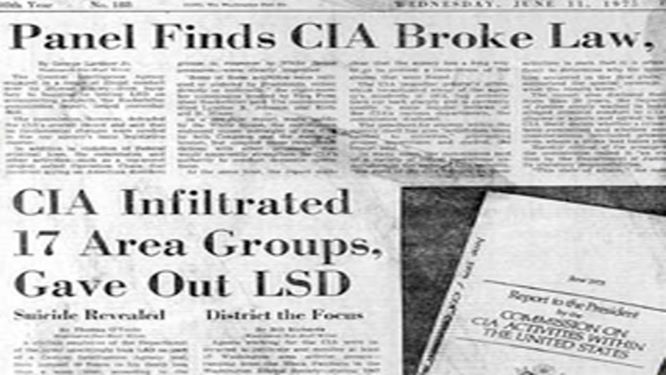

This week I will be featuring the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) organization that was founded by Rick Doblin in 1986. I have mentioned this organization several times throughout prior blog posts, but this one will go into greater depth about the organization and the founder. Healthcare financing and strategies for sustaining innovation will be the primary topic and is relevant because Rick and his organization have firsthand experience with both financing and innovation in the world of psychedelics. MAPS is a 501(c)(3) non-profit research and educational organization. This means that it has been approved by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as exempt from federal income tax and that individuals can take a tax deduction on any donations to the organization. MAPS relies on the donations of individuals because no funding is available from governments, pharmaceutical companies, or major foundations. 501(c)(3) organizations are prohibited from supporting political candidates or conducting political campaign activities. However, they can lobby but can lose their tax-exempt status if a substantial part of activities is attempting to influence legislation (IRS, 2019). Involving themselves in issues of public policy, such as educational meetings or seminars, is not considered lobbying by the IRS (IRS, 2019). Interestingly, MAPS owns a subsidiary called MAPS Public Benefit Corporation (MAPS BC). A Public Benefit Corporation (PBC) pays taxes, operates for profit, spends profits on a specific benefit to the public, and is intended to be more transparent, sustainable, and accountable than a traditional corporation (Stracqualursi, 2017). The financial reports consolidate information from MAPS and MAPS BC. The 2017-2017 fiscal year showed approximately $5.9 million in net revenue from donors, events, sales, grants, and investments (MAPS, 2017). About 50% of that came from individuals and family foundations (MAPS, 2017). Rick stated that there might be fundraising challenges on the path to FDA approval for the prescription use of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as the project needs approximately $26 million to complete Phase 3 trials. He emphasized the need to discuss the potential commercialization of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, particularly with the recent epidemic that has increased social stress, anxiety, depression, and trauma. Likely, the need for treatment and subsequent access to coverage through insurance will increase once the treatment is approved by the FDA. His goal is to obtain insurance coverage for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy and then obtain prescription use and insurance coverage for other psychedelics. MAPS is innovative to its core, as the very idea of psychedelics in therapy goes against current mainstream thinking. MAPS has chosen an anti-patent strategy to support the benefit for humanity. They do not oppose for-profit companies but believe that non-profit and PBC’s can help keep the focus on patients first and profits second. With the current situation regarding COVID-19 some of MAPS clinical trials have been postponed. It is unclear what impact this may have on the projected Phase 3 trial completion (anticipated for 2021) and subsequent FDA approval (anticipated 2022).

Financing and strategies for sustaining innovation are important for any organization to discuss. Particularly in times of uncertainty or economic downturn like we are currently experiencing. The ability to adapt, modify, and change processes quickly is important for survival.

References

MAPS. (2017). FY 2016-2017 financial report. Retrieved from https://maps.org/about/fiscal/7193-fy-2016-2017-financial-report

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). (2019). Lobbying. Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/lobbying

Stracqualursi, M. (2017). The rise of the public benefit corporation: Considerations for Start-UPS — BC law lab. Retrieved from https://bclawlab.org/eicblog/2017/3/21/the-rise-of-the-public-benefit-corporation-considerations-for-start-ups